Christopher Marlowe anagrams at

William Shakespeare's burial place

in Holy Trinity Church,

Stratford-upon-Avon

The Shakespeare Epitaphs

By Roberta Ballantine

SUMMER 1996 SHAKESPEARE

BULLETIN – 25

Editors' Note: While Shakespeare Bulletin is

not intended to be a forum on the authorship issue or an arena for

anagrams, we thought the following article sufficiently curious and

provocative to warrant its publication.

Engraved on the flat stone covering William Shakespeare's

burial place in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church,

Stratford-upon-Avon, is this familiar jingle, thought to have been

written by Shakespeare himself (1):

GOOD FREND FOR JESVS SAKE FORBEARE,

TO DIGG THE DVST ENCLOASED HEARE!

BLESTE BE YE MAN YT SPARES THES STONES,

AND CVRST BE HE YT MOVES MY BONES

When the letters of these verses are carefully rearranged, keeping

connected letters together and abbreviation intact, a ferocious message

appears—an anagram which has never been made public:

BENEATH YE CLOSE FIND

MARLOVES VERSE,

NEAR SHAKESPEARES DVSTY BONES,

O YT BRAGGART JESTE OF GODD

BE CVRSD!

HE YTS ENTOMBED OF THESE

STONES.

M

Anagrams are often derided as meaningless games, for a popular

notion holds that any sequence of letters containing a possible variety

of words can be rearranged to form all sorts of different messages. Not

so! Sometimes the letters of a randomly chosen word sequence can be

shifted to create a number of different words, but unless that sequence

is the outward form of a truly created anagram, letter-shifting, even

if some related phrases are achieved, always results in a longer or

shorter residue of meaningless letters or, at best, irrelevant words.

A real anagram is a respectable and sometimes very useful cipher.

When meaningful communication emerges, which uses the material given

out front, including abbreviations, single letters, and connected

letters, and especially when the communication makes assurance

double-sure by using meter and rhyme, it can be judged a correct

decipherment. But it is true that certain anagrams, after their words

are correctly formed, may be slightly rearranged, altering the message.

In this secret poem on the floor of the chancel, the words MARLOVES

and SHAKESPEARES can be exchanged. The transfer doesn't make sense

— the grave is Shakespeare's — but the fault may have moved the poet to

make a second epitaph, one more tightly crafted, free of ambiguity.

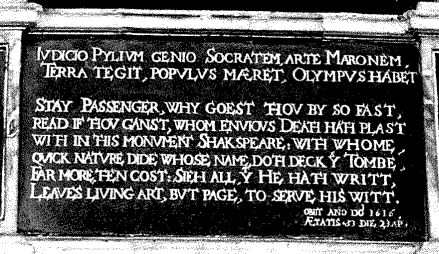

On the north wall of the chancel in the same Holy Trinity Church,

carved into the facing-stone below the bust of Shakespeare, there's a

message in verse that has puzzled its readers for centuries. (2) It contains an

obvious spelling error (SIEH should be SITH), and, after its eloquent

opening lines, the poem deteriorates into a tangled contrivance which,

though it makes labored sense, leaves the reader feeling uncomfortable.

Scholars patiently explicate the convoluted phrases and attribute both

SIEH and the poem's odd punctuation to a poorly-schooled stonemason.

But the handle of a cipher sticks out here: DIDE could be DIDO with

substitution of a single letter. Trial and error letter-shifting slowly

solves the puzzle, and a touching poem appears — six meaningful lines,

Shakespearean in tone, rhyming ababcc. As he's done in the cipher on

the chancel floor, in this longer poem the author manages to help the

decipherer by connecting some letters that take their places next to

each other in the secret verses: many TH' s, two ME 's,

and an NT. The word NAME goes across intact, as do THIS and

HIS. The abbreviations, using s over Y and t over Y, were in common use

when this composition was made — they stand for THIS and THAT—and WRITT

and WITT, minus their extra T's, keep their positions in the final

couplet.

Here's the public version first, then the secret one:

STAY PASSENGER, WHY GOEST THOV BY SO FAST?

READ IF THOV CANST, WHOM ENVIOVS DEATH HATH

PLAST,

WITHIN THIS MONVMENT SHAKSPEARE: WITH WHOME,

QVICK NATVRE DIDE: WHOSE NAME DOTH DECK Ys TOMBE,

FAR MORE THEN COST: SIEH ALL, YT

HE HATH WRITT,

LEAVES LIVING ART, BVT PAGE, TO SERVE HIS WITT.

WAS MARLOVES STAR ENTOMBD, BY THIEVES,

WITHIN THIS CRYPT? THE EPITAPH YT

DECKS THIS CLOSE,

FRAGMENT THAT: SEE THROVGH, KNIT VP, THE

WOOLSEY WEAVES

OF QUEEN DIDO, KING LEAR: IN BOTH, ONE AVTHOR SHOWS,

WHOSE ART HIS NAME WITH LOVE HATH WRIT:

THAT FACT MVST SAVE YS DAMNED,

SAVAGE WIT. H

The author inverts one M, using it as a W (I've underlined it), and

may have taken advantage of a rule mentioned by William Camden in his

chapter on anagrams in Remaines Concerning Britain, first

published in 1605. Camden writes: "The precise in this practice

strictly observing all parts of the definition [of an anagram] are

onely bold with H either in omitting or retaining it, for that it

cannot challenge the right of a letter" (168). The H at the end of the

long anagram may be the author's initial, but the strong Marlovian

rhythm that moves the lines suggests the work was crafted by the poet

himself, mindful of Camden's rule.

And here in this anagram there's no dangerous equivocal construction

to threaten clarity of meaning. THIS and THAT, if exchanged, make only

a subtle difference in nearness. The penultimate line can be read

WHOSE ART HIS NAME WITH LOVE HATH WRIT, or,

WHOSE NAME HIS ART WITH LOVE HATH WRIT.

The meaning is the same; the poet might have made the words

interchangeable to emphasize that crucial line.

This anagram may be the longest in existence, for even counting YS and YT as

only two, the work contains two hundred eighteen letters, and,

according to cryptographers William and Elizebeth Friedman, the longest

known anagram is a poem in Spanish containing eight lines of verse but

only "about 140 letters" (93). It is also remarkable that every one of

the many punctuation marks in the "Stay Passenger" poem is fitted into

a suitable place in its anagram.

But shows of literary panache are not the true wonders of this

work. Its significance lies in its meaning, along with the nature of

its medium. The author must have believed the only way to preserve his

message so it might someday be understood would be to have it carved in

stone, in cipher, and installed in a public place.

His communication is succinct. Though the poet was a damned savage,

he created all his writings with love, and the style of his art must

reveal him as author of the whole range of youthful Marlowe,

mature Shakespeare work. For the world to recognize

his authorship was so important to him he felt it would save his soul.

It could happen. Someday passengers might stay, and read, and the

ghost could rest. (3)

Notes

1Differing

scholarly opinions hover over the punctuation of the gravestone

epitaph. B. Roland Lewis, in The Shakespeare Documents

(2:529), states that due to chipping of the stone over many years the

originally carved marks may have suffered alteration, and he declares

there is no exclamation point after the second line, as E. K. Chambers

printed it in 1930 (2:181). Lewis makes it a colon, and others have

made it a period. Nevertheless, the rubbing that Lewis displays as

Document 249 (see 530-31) clearly does show a crude but identifiable

exclamation point after line two, a reading that certain scholars

continue to endorse (e.g. Wadsworth 17).

Some of the letters incised on this stone have also

been cause for debate: the word BLESTE, some say, is really BLESE. S.

Schoenbaum, in William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life

( 250), prints BLESTE but mentions BLESE as "a possible alternative."

So does G. Blakemore Evans in The Riverside Shakespeare

(p 1834). In The Shakespeare Documents, Lewis, after

a convoluted description of the appearance and position of the word,

asserts that there is no stem of a T leaning up against the last E,

reaching out an arm to touch the S that precedes it. "Even though the

stone has been chipped at the point in question," he writes,

"magnification of the final E reveals no outer left shank off a capital

T" (2:529).

But, once more, the rubbing he provides refutes his

statement. It does not show an elegant shank complete with serif; it

does show a clear white line — not a "chip" at a "point" — running from

the top of the final E back to touch the crown of the S preceding it.

(And how about the meaning of the word?)

Lewis does mention joined letters in the

inscription. Except for this trinity of STE, which he doesn't

recognize, all are in twos, and all of them, including this triad, go

across intact into the secret message. That's why they're connected —

to make it easier for the decipherer. STE becomes part of the word

JESTE , on the secret side.

Back

2For photographs

of the gravestone and monument inscriptions, see

Halliday 127 and 116. Back

3 Decipherment

of both epitaphs is copyrighted by Roberta Ballantine. Back

Works Cited

Camden, William. Remaines Concerning Britain.

1605. Rpt. London: S. Waterson and R. Clavell, 1657.

Chambers, E.K. William Shakespeare: A Study

of Facts and Problems. Vol. 2.Oxford: Clarendon P, 1930.

Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. The Riverside

Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin,1974.

Friedman, William and Elizebeth S. The

Shakespearean Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1957.

Halliday, F.E. Shakespeare: A Pictorial

Biography. London: Thames and Hudson, 1969.

Lewis, B. Roland. The Shakespeare Documents:

Facsimiles, Transliterations, Translations, & Commentary.

Vol. 2. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1941.

Schoenbaum, S. William Shakespeare: A

Documentary Life. New York: Oxford UP, 1975.

Wadsworth, Frank W. "Shakespeare's Life." In the

Pelican edition of The Complete Works. Gen. ed.

Alfred Harbage. Baltimore: Penguin, 1969. 10-18.

|

POSTSCRIPT

There's more to this story.

Deciphering the epitaphs, I used a transcript of the chiseled letters

of the six-line poem, published in the Riverside Shakespeare,

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974. p. 1834.

In the six-line poem shown

there, a connect-the-dots message is available when punctuation-marks

in the poem's middle section are used as dots: A line starting at the

top left comma, drawn down through the comma after "canst," then out

around the colon at the end of the word "Shakspeare" and back to the

colon after "Dide," waving down through the colon after "cost" and the

comma after "art," creates a crude phallic outline labelled inside;

"Shakspeare." Another line, circling the punctuation of

` ": sieh all,

, but page,"

provides a small pool below. On

p. 231 of his book, A Perfect Spy, John Le Carrè uses

the phrase "a load of cock" as spy-slang, and the marks waiting to be

connected on the epitaph's verses suggest that the out-front creation

is a "load of cock," and that we should look deeper into the poem,

constructed, as a spy would understand, as a "dead-drop." (Click for a

sketch of the Riverside Shakespeare

picture.)

But in 1974, the same year my Riverside

Shakespeare was printed, the caretakers of the Stratford monument

announced that the six-line poem had been vandalized. Had someone

connected those punctuation marks, and the shocked curators felt they

must erase the possibility of another such occurance? Because a

stonemason came in to make changes: The colon after the word DIDE was

deleted; the word CANST in the second line was altered to read GANST,

and the question mark at the end of the first line was erased. Removal

of the colon after DIDE destroyed the possibility of meaningful

scraffiti on the front—the alteration of C to G destroyed, in one

stroke, the entire inner message itself.

The Carved Poem as

Revised in 1974

The Carved Poem as

Revised in 1974

Here's a clear picture of the

poem which all post-1974 visitors to the church have viewed: no

question mark at the end of line one—no colon after the word Dide.

Canst has become Ganst, and two haphazard slashes have been added in

the right hand margin (as if to show the workman unskilled?) I was

fortunate to find the honest transcript in the Riverside

Shakespeare, showing all readers the form of the original six-line

poem, its inner message intact—a masterpiece of steganography. True

restoration, not redecoration, should be called for by students of

antiquities.

The two Latin lines carved just

under the niche have not been tampered with, and they, too, were

composed in memory of Christopher Marlowe. They have an inner

message—in English—and are signed—surprise!—by Kit's half-brother Peter

Manwood. The outside message contains these references:

PYLIVM. Pylius is a poetic way

to say Nestor. Nestor's father, a great judge, was executed because he

disagreed with the government, and Nestor was to have been executed,

too, but escaped. The story parallels Marlowe's experience.

SOCRATVM. Socrates was a

bi-sexual man who married late and had children. Kit's second marriage,

and a family, came in his middle age. Socrates died for keeping faith

with his ideals; so did Kit Marlowe.

MARONVM. Virgilius Maro was a

spy poet who made secret writings, often amusing ones. Kit, too, was a

professional intelligencer who created many poetic works, each

containing secret writing.

Here are the Latin lines with

translation:

IVDICIO PYLIVM, GENIO

SOCRATEM, ARTE MARONEM

TERRA TEGIT, POPULVS MAERET,

OLYMPVS HABET

(In Judgement a Pylius, in Genius

a Socrates, in Art a Maro. The Earth Buries Him, The People Mourn Him,

Olympus Possesses Him)

And the inside message reads:

YES, EAGER T-TO AID CIVIL

IMPROVEMENT, BRIGHT MARLOVE VVROTE IMMORTAL PLAYS 'N' POEMS. PETA

(Interesting that at this early

date Peter thought of his half-brother's writings as immortal.)

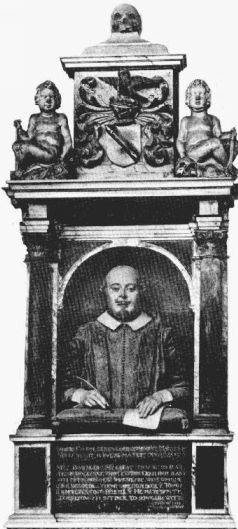

Everything about this monument

can be viewed as a tribute to Marlowe: the half-figure in the niche

could be an earnest copy of young Martin Droeshout's engraving of a

Marlowe portrait. (Perhaps the Venice Portrait?)

The pose of the Stratford

personage is the same as that of Marlowe's father's statue in the niche

of his own monument at St. Stephens. The two monuments share their

style of architecture, though Roger Manwood's is more costly and

elegant.

The Stratford-on-Avon statue

wears an extraordinary number of buttons—29, which might represent the

29 years Marlowe lived in England and his 29 years of exile.

Above the niche, two putti

hold symbolic tools—the boy on the right holds an extinguished torch,

representing art creation now ended. The child on the left grasps a

shovel, which could signify all the dirty jobs the poet did for SSS.

Between the cherubs stands a

mysterious big box, bearing in bas-relief a coat of arms with a pen and

in the background an elegant black helmet—Pluto's Helmet? In his Promus

of Formularies, Bacon declared that Pluto's Helmet made you invisible,

and Kit Marlowe was invisible for 29 years. The helmet is surmounted by

a very small raptor (perhaps with a broken wing?) which might be a

merlin. (Merlin was a college nickname of Marlowe's.)

Is the box a real ossuary, or

just a symbol of one? On top of its pyramidal cover rests a real

skull—its lower jaw embedded in cement, a septum in the nose, some

missing upper teeth, eyesockets large, widespaced.

People often mention that

William Shakespeare's death in April 1616 didn't bring forth any public

mourning—no monument was erected to honor him then. It was six years

later, in 1622, after Marlowe's death—Gregorio de' Monti's death—in

November 1621, that this monument appeared, ostensibly for Shakespeare.

Was it made by friends of Kit-Gregorio? Though the construction didn't

cost a lot of money, all its parts strongly suggest it was put together

with loving thought in memory of that writer, Christopher Marlowe.

|

The Home page of Roberta Ballantine's site dedicated

to Christopher

Marlowe

Contents of Roberta Ballantine's site dedicated to Christopher

Marlowe

Roberta Ballantine

e-mail: bertaba@comcast.net

954 Virginia Drive, Sarasota, FL, 34234, USA

Copyright © 2003 Roberta Ballantine

All rights Reserved